and then he asked "So ... when did you finally learn to draw?"

Jul 23, 2023

July 23, 2023

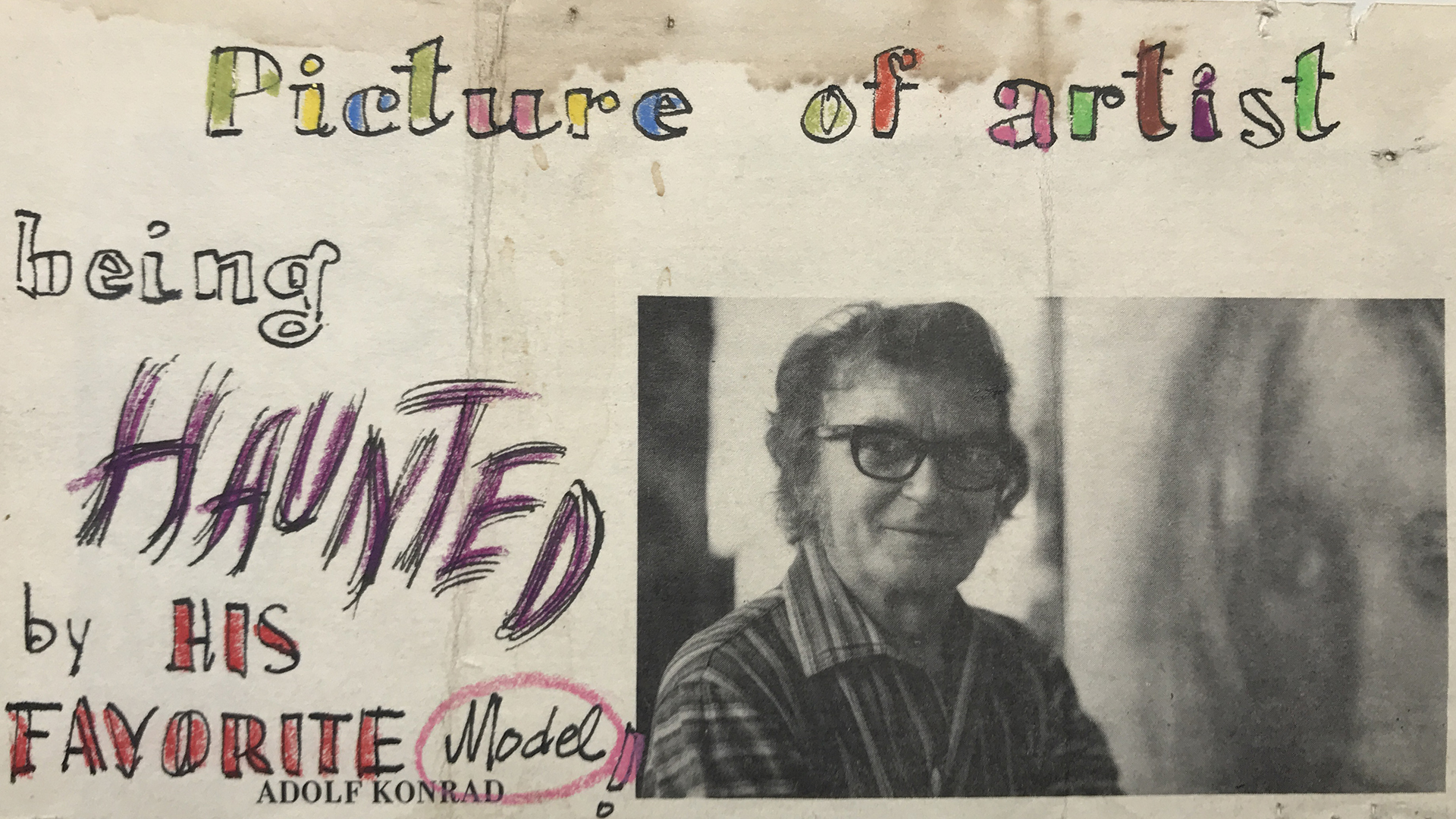

I was his favorite muse ... or so he said. I sought him out after seeing a beautiful and haunting painting above the grand piano in the home of a young girl called Silly Stein. I'd taught her to build a raft and paddle through Skinners Falls on the Delaware River.

It wasn't until much later that I realized I'd grown up admiring Konrad's sketch of musicians in the home of my best friend.

Ink and Gouache on kraft paper

I had no interest in being Konrad's muse and model. I wanted to be his student. I wanted to learn everything I could from him. I was nineteen years old. At the time, I was attending a commercial art school, Spectrum Institute for the Advertising Arts. I was utterly miserable. Yes, I was learning how to use ruling pens, ink, watercolour, gouache, acrylic, oil, charcoal and wolff pencil. I learned paste up and mechanicals. I learned how to use photographs in the file drawers called "the morgue" and use them for reference. Everything was a copy of something, never an expression of my thoughts, feelings or dreams. The world of artists that I wanted to be part of was dismissed. And so, after a month of taking evening courses with Konrad, once a week at an art center in Bernardsville, New Jersey, I left the commercial art school. During the day, I jabbed hypodermic needles down the throats of lab rats and at night I painted.

The next summer, I attended a workshop in Ogunquit, Maine with a group of much older artists, mostly retired from their lifelong jobs at one thing or another. It was glorious, painting en plein air each day, eating, drinking and sleeping art. Conversations over breakfast and dinner were inspiring and thought-provoking. I watched Konrad sketch. There was hardly a moment when he didn't have either fountain pen or brush in his hand. He sketched on napkins while waiting for our food to be served. He sketched as we talked together after dinner. He sketched everything ... spoons, lamps, rocks, chairs. And then one night, Hurricane Agnes hit. We lost power. We painted and sketched by candlelight, drank whiskey and listened to the news on transistor radios. It was early June of 1972.

left to right: Adair (eventually married to Konrad), Chris Carter, Nancy Rickert - I was painting a small oil sketch of Konrad as he was painting this oil on wood sketch of the three of us ... before the hurricane hit.

It was during the aftermath of the storm, that Konrad sketched this portrait of me using charcoal sticks and a facial tissue on a large, linen canvas. It was later sold to an executive and hung in his office on Wall Street. Decades later it found its way back to Konrad. After his passing in 2003, Adair gifted me the portrait. Such a long journey, both for the portrait and for me.

Konrad encouraged all of us to sketch. To sketch everything. To sketch everywhere. To sketch from life, from the world around us. I never saw him sketch from a reference photo, though I'm sure he must have used references for his paintings of Victorian houses and buildings in the Ironbound district of Newark.

My drawing skills were marginal and I didn't enjoy sketching at all. It was frustrating and not at all satisfying. What I know now is that I was simply trying too hard. I was working at drawing rather than playing with my tools and media. Instead of allowing my pen to dance across the paper, either quickly or slowly, I had burdened it with my expectations. Those expectations were like a ball and chain, keeping my hand and spirit imprisoned in a false illusion of how and what I thought I should be drawing.

In 1973 I left my job as a lab technician and, with Konrad's encouragement, I left New Jersey and moved to Boston, running away from my disappointment in having become a muse rather than a blossoming artist. It was clear to me that I was a long way from earning the respect of my mentor. His parting words were "Christine, you must learn to draw."

I tried. I tried really hard to sketch more. It was slow and laborious. My eyes were always dashing about from shape to shape, colour to colour, line to line, as my mind pieced together the shapes, colours and lines to create spiraling, kaleidoscopic images that delighted me and distracted me from my task of learning how to draw. I made excuses ... it's the wrong paper ... wrong sketchbook ... wrong pen, pencil, brush, ink, paint.

Thirty years late, I had sixty-six incomplete sketchbooks collecting dust on my shelves. Somewhere, at some unrecognized point in time, I learned to draw. I had learned to allow my inner artist to discover who she is and what delights her. I allowed her time to play, time to experiment and time to enjoy the act of drawing ... the process ... without passing judgement on the results.

Those thirty years were bumpy. While in art school in Boston, I gave up the notion that I was an artist, that I would ever succeed as an artist. I felt like a fraud. Twice over the next decade I gave away almost all of my art supplies. I threw most of my paintings and drawings in the local dump. I didn't want reminders of my failures. My inner artist ignored my efforts to silence her.

I found it impossible to stop creating lines. I didn't need pencils, pens or brushes. I would pick up a broken shell and draw swooping lines in the wet sand of a beach, responding to the sound of the gulls and the waves lapping onto the shore. I drew on rocks and boulders with the charred bits of wood from an evening campfire. I carved into my mashed potatoes with a spoon and watched my cream slowly spiral into my morning coffee.

Perhaps it was my apprenticeship with photographer Eileen Toumanoff that strengthened my inner artist and kept her from being silenced. During my time in Boston, I learned more from black and white photography, about myself and the elements of art, than I did from sketching. I had acquired self-taught darkroom skills from the nights during high school when I turned the family kitchen into a darkroom after the sun went down. Eileen introduced me to the Zone System, strengthening my understanding of the importance of grayscale tones. In addition to the tasks of developing her film and printing all her work prints, I had assignments to research the work of specific photographers in the archives of the Peabody Museum in Cambridge. My eyes and brain were thrilled with puzzling together the shapes of whites, blacks and grays without the agony of defeat as I experienced when sketching.

Upon graduating from Massachusetts College of Art, I felt split. The prospect of becoming a photographer was far better than that of becoming a painter. Neither was promising. I had no plan and very little of worth to call a portfolio. I opted to become a rock climber instead.

Life's experiences never go to waste.

I continued to start new sketchbooks only to abandon them.

In spite of my poor relationship with sketching, I was hardly ever without a sketchbook and a pen. I filled moments of waiting for one thing or another, and moments of nothingness with sketching. I often had flashbacks of watching Konrad sketch his silverware on a placemat or napkin. It was simply something I did. I sketched. Maybe I sketched more often because I had all but given up the idea of becoming an artist. I no longer felt pressure to draw well or to prove anything to anyone or to myself. Sketching became something I actually enjoyed doing. I fell in love with contour drawing because my pen could dance across the paper as my eyes explored the form of an object and the lights and shadows on the object.

Like most everyone else, I had to make money. I needed a roof over my head and food for my body. My skills were both extensive and limited. I could change the brakes on my car, install plumbing and electricity in buildings, unravel knots, create Caesar salad at a customer's table in high end restaurants, maintain live plants in commercial buildings, ...I was indeed, a Jack of all trades and a master of none.

I occasionally took on commissioned art work, never trusting that I could please my clients. I managed to get by doing pet portraits, a few people portraits and house portraits. Thanks to my father, I learned perspective at a very young age . He was an engineer.

... Two decades later, my experience doing dog portraits, and the years of sketching in all those incomplete sketchbooks led to writing and illustrating a children's book, The Collie of Castle Hill. The illustrations were done in pencil on cream paper, reminiscent of the children's books in the 50's when the story takes place. By this time, I'd moved more than thirty times, had three children and found myself back in New Jersey living less than ten miles from Adolf Konrad. He had stopped painting due to his diminishing eyesight. I brought him a copy of my book.

He took it in his hands a bit reluctantly, perhaps feeling pressure to say something nice to me about it. He wasn't one to compliment when a compliment wasn't deserved. He opened the thin book. He pulled it closer to his face, then walked into his studio with it and picked up the magnifying loop from his drawing table. Slowly, very slowly, he explored the illustration he had opened to. He turned pages and looked carefully at the trees, the buildings, the water, the young boy and the collie. The corners of his mouth turned up ever so slightly. He paused, lifted his head, looked me straight in the eye and asked, "So ... when did you finally learn to draw?"

Until that moment I hadn't realized the gift he had given me all those years before when he encouraged me to go to Boston and to learn to draw. I hadn't realized that my determination to earn Konrad's respect had held the bar so high that no matter what skills I gained, I continued my journey toward mastery. It was only mastery of one kind or another that would earn his respect. With those words, my mentor set me free. I was no longer just his muse. It was with his passing that I realized the importance of mentoring, of passing on both the quest for knowledge and the never-ending journey of acquiring skills that become part of the creative process, a process unique to each artist.

Still, he has set the bar high. Would I earn his respect as a mentor?

Thank you for reading my blog.

Chris Carter

Join The Arttist's Community to inspire and be inspired.

Subscribe

Join my mailing list to receive notification of new blog posts and update on the online courses.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.